Understanding what makes artwork valuable

Today, we’re exploring what makes artwork investing so alluring.

In addition, we did a podcast with Michael Wenner, VP Marketing at Masterworks. Masterworks is a platform allowing anyone to invest in contemporary fine art. They’re doing a ton of heavy-lifting advertising right now, and in turn, are helping push the whole alternative investment industry forward.

Let’s explore ????

Table of Contents

The history of fine art collecting

Fine art is arguably the “oldest newest” alternative asset.

Wealthy investors have been collecting fine art for hundreds of years. So it only makes sense that, along with more traditional alts like farmland and wine, fine art was in a great position to capitalize upon the recent Cambrian explosion of fractionalization.

The practice of art collecting is almost as old as civilization itself. We’re talking thousands of years here. While slaves were building the pyramids, ancient Egyptians were burying King Tut with their lapis lazuli & gold, demonstrating their culture’s taste and style to the Gods.

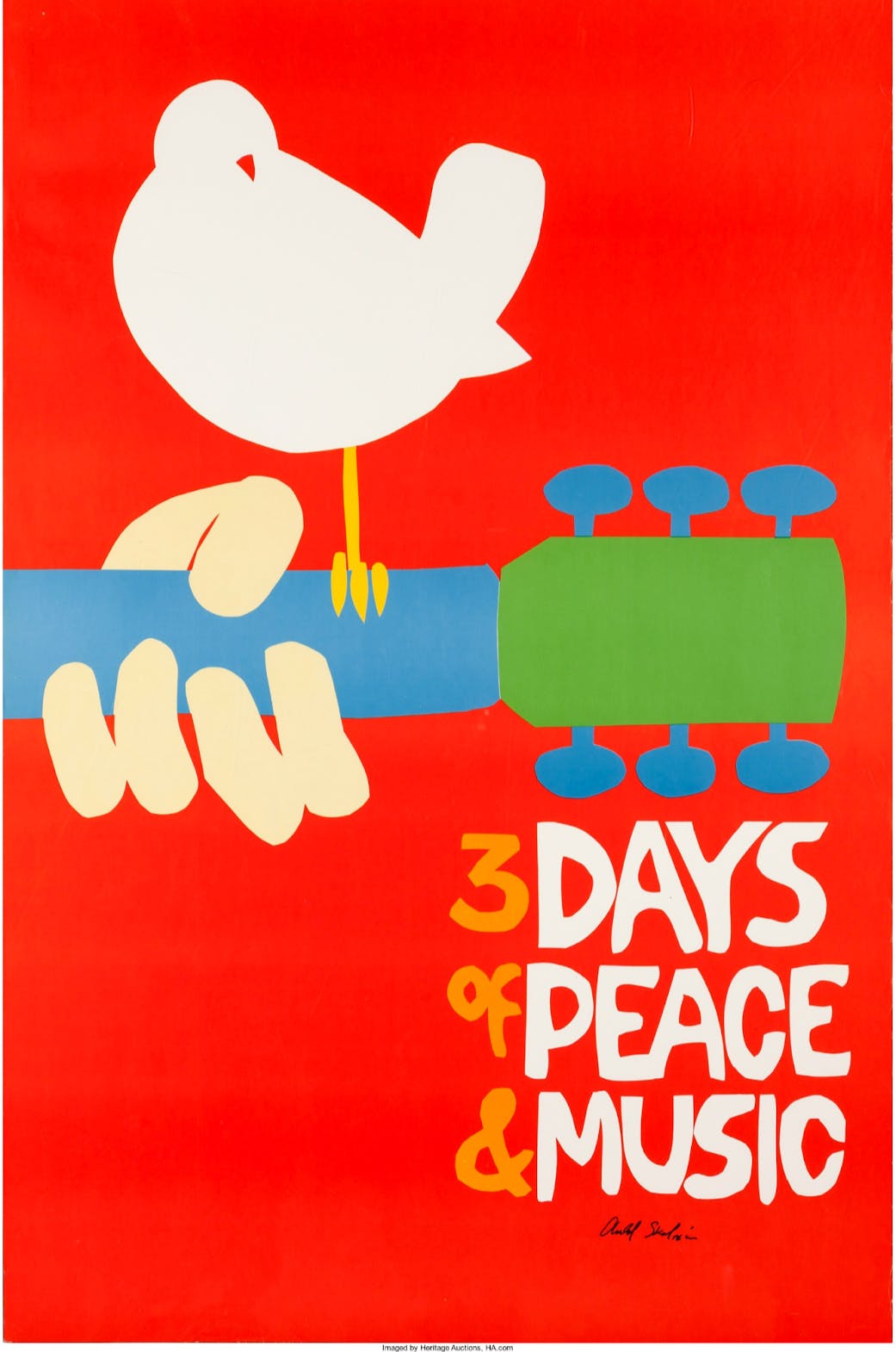

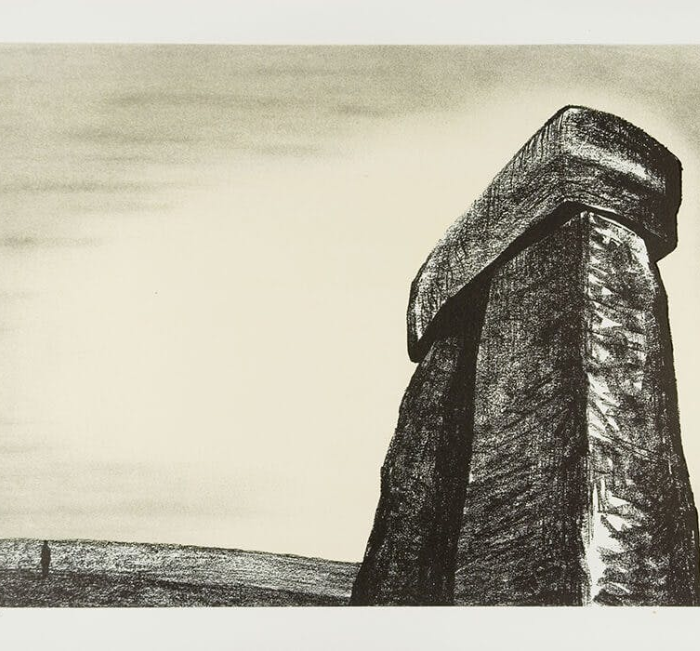

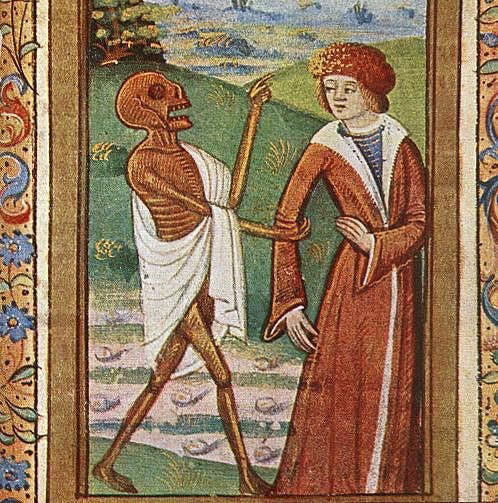

When Rome fell, the barbarians sacked the cities, and basically ruined everything. They didn’t manage to kill off fine art completely, of course. But for over a thousand years, art entered a dark, subdued period; rich in religious imagery and lacking excitement. Paintings from the middle ages (500-1400) carry an especially depressing tone. Lots of skeletons, demons, snakes, and creatures of death.

During this time, artwork was commissioned solely for wealthy families and institutions. Don’t forget — paint was expensive, and talent was scarce. Unless you were a Hapsburg or other royalty, it’s highly doubtful you or anyone you knew owned an oil painting.

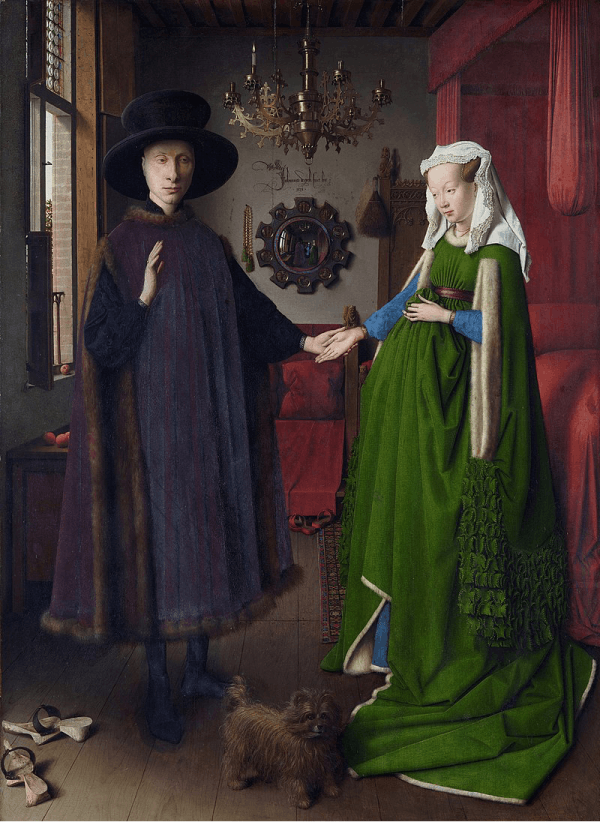

Excitement for art collecting kicked into high gear once again during the European Renaissance (1400 – 1600). This era saw epic works such as The Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, as artists started taking more creative risks. Religion was still a huge theme, but artists were pushing boundaries and gaining fame. Da Vinci. Carvaggio. Bosch. Van Eyck. These were essentially the world’s first art rock stars. ????

How fine artwork is bought & sold

After a while, artists began to realize there were quite a few rich folks who wanted to buy their works, and the first public art markets began to sprout up.

Auction houses

The Stockholm Auction House was the world’s very first auction house when it opened in 1674. The auction house is still around today 347 years later, where it does a respectable $57 million in turnover per year. It is owned by Swedish online auction house Auctionet.

British auction giants Sotheby’s and Christie’s made their debut 80 years later. Although Sotheby’s didn’t actually start dabbling in art until the 1900s, it has sold many famous paintings, including Warhol’s Orange Marilyn, and to this day remains the oldest company listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Both companies have become synonymous with fine art, collectibles, real estate, and dozens of other luxury goods. Every day goods may be auctioned on eBay or bought on Amazon. But the world’s rarest, most valuable items are almost exclusively sold through one of the major auction houses: Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Heritage, Philipps, and China Guardian.

Christie’s is the world’s largest auction house, and has broken countless records over the years. It is privately owned by Frenchman François Pinault; a self-made businessman and art collector, whose net worth of $58 billion puts him at #21 on the world’s richest people list.

They’ve created an online auction division, where pretty much anyone can register and bid on works. This has especially helped them during COVID, as older clients learn to trust this new medium.

Private sales

About half of all artwork is done through private sales. These “off-market” transactions make tracking sales history and determining valuations much more difficult. But it’s the preferred method of transacting for many collectors, who wish to keep their activity and holdings anonymous.

Art dealers typically own galleries and have large private collections, which they use to sell directly to buyers. They often travel internationally, going to auctions and studios looking for good buys, hidden gems, and exciting, undervalued works.

Art brokers are often dealers or other private artwork experts who utilize their network + market experience to source and negotiate purchases for serious buyers. Similar to real estate agents or website brokers, they advise on timing, assess value, and perform due diligence; typically charging a commission only when a sale is made. Fees of 5% to 20% are usually charged to the sellers, though some do the opposite, charging buyers a “finders fee.”

There are at least 10,000 art brokers in the US alone. Given the high price of rare artwork, those with a passion, art education, and specialized knowledge of a specific period or style can do quite well for themselves.

Over the past 15 years, online art brokerages have commanded significant web traffic. The most popular online brokers are MyArtBroker.com and ArtBrokerage.com

What are the most expensive paintings ever sold?

The most expensive painting ever sold is the Salvator Mundi, which was sold at a Christie’s auction in 2017 for $450 million.

Salvator Mundi is a Leonardo Da Vinci painting that has been dubbed “the male Mona Lisa.” The buyer was none other than MBS — the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman.

However, the painting is extremely controversial. It goes beyond art history and into geopolitics. Intense X-ray and infrared evidence suggested that Da Vinci didn’t actually paint this himself, but rather only made a contribution to the painting. French experts stated it was more likely to have been painted by Da Vinci’s assistants, while Leo “instructed and added touches”.

The French notified the Saudis, who were understandably pissed. MBS demanded the painting be authenticated, in order to save face & preserve the value of his investment. Oh, and nobody even knows where the painting is anymore! The whole story is wild, and is the subject of an upcoming documentary called The Lost Leonardo.

The five largest painting sales ever recorded are:

- Salvator Mundi, by Leonardo Da Vinci (sort of). Sold to MBS in 2017 for $450m

- Interchanged, by William de Kooning. Sold by David Geffen in 2015 for $300m

- The Card Players, by Cezanne. Sold to the country of Qatar in 2011 for $250m

- Nafea Faa Ipoipo, by Paul Gauguin. Sold to the country of Qatar in 2014 for $210m

- Number 17A, by Jackson Pollock. Sold by David Geffen in 2015 for $200m

What makes a piece of artwork valuable?

Man, that is a loaded question. An artist’s creation can be a beautiful thing, and yet not have a high monetary value. And vice-versa! Plenty of ugly paintings have sold for millions. (Heck, just look at Jackson Pollock.)

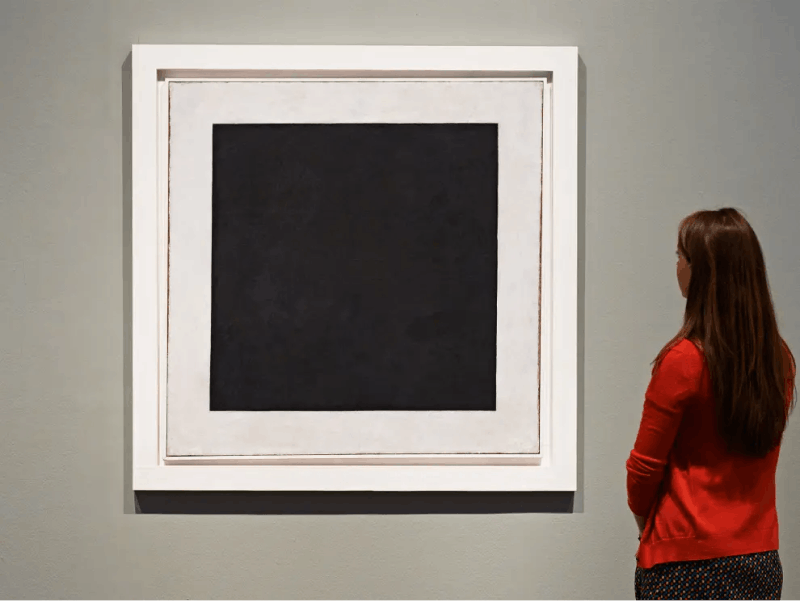

Modern art can be especially divisive and controversial. But remember that what looks simple can be the culmination of a lifetime’s worth of work. For example, Kasimir Malevich’s The Black Square is simple, but it took 20 years. The painting was confiscated by Stalin and he was jailed for two months for making it. That matters.

We’ve seen this phenomenon play out recently in NFT art markets, where select squiggly line NFTs are selling for over $100k, and people are scratching their heads as to why. While that example is a bit ridiculous, Beeple’s massive $69 million JPEG, The First 5000 Days, took him, well, 5,000 days to create!

The point being, there is often a tremendous disconnect between time, effort, popularity, sentiment, scarcity, and the “market value” of artwork.

Ultimately, value is in the eye of the beholder. A painting is only valued at what someone is willing to pay for it. Still, artwork value is built upon several overlapping and intricate factors. And while these often escape the understanding of traditional investors, here is a rough guide to help you understand value.

Artist recognizability

The artist is the biggest determinant of value, by far. To use a parallel with real estate, a one-story shack in Beverly Hills, California has more value than a 3-story home in Flint, Michigan.

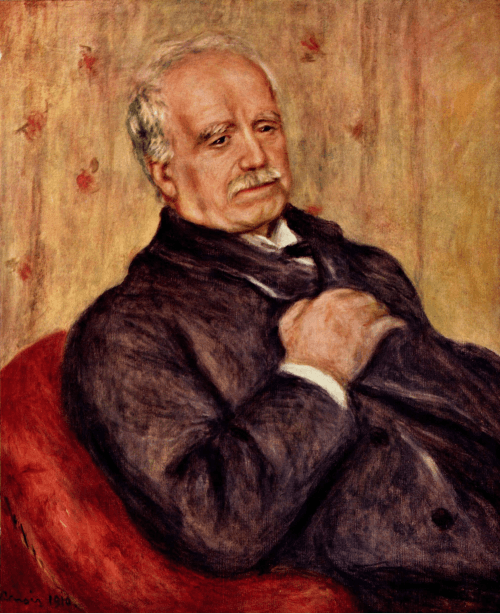

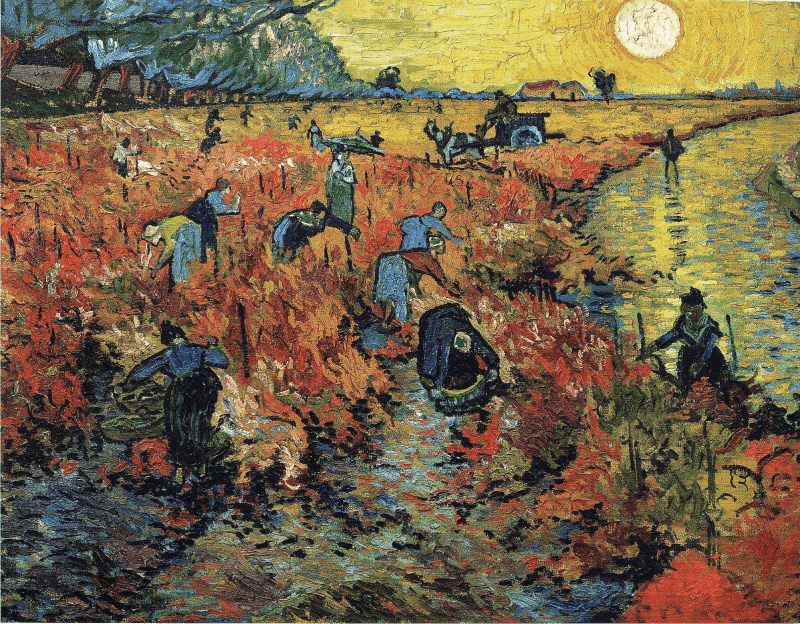

The same principle holds with artwork. Who the artist is matters much more than what the artist has painted. Popularity certainly changes over time, Vincent Van Gogh is one obvious example. He didn’t find success until a hundred years after he died.

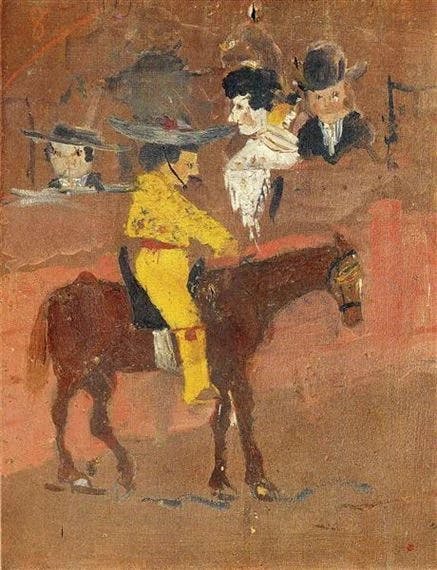

But recognizability is ultimately the most important factor. The worst brush strokes Picasso ever made will always fetch more than, say, your son’s fridge art. That’s just the way it goes.

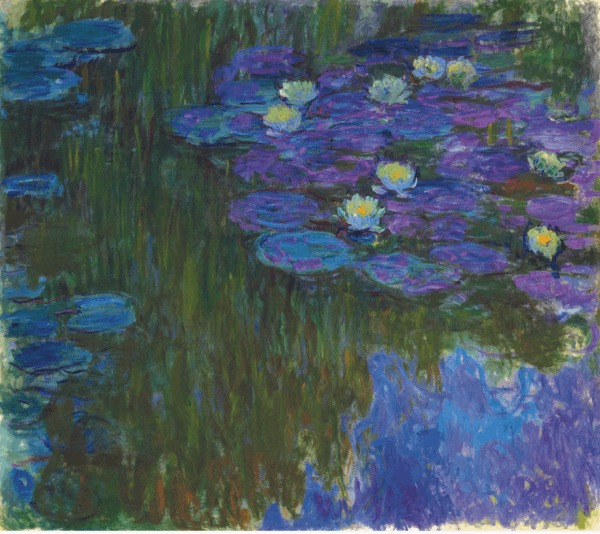

Medium

What materials did the artist use? Canvas is almost always worth more than paper. Oil is generally worth more than pastels. Then comes watercolor, followed by pencil, then charcoal, and finally prints.

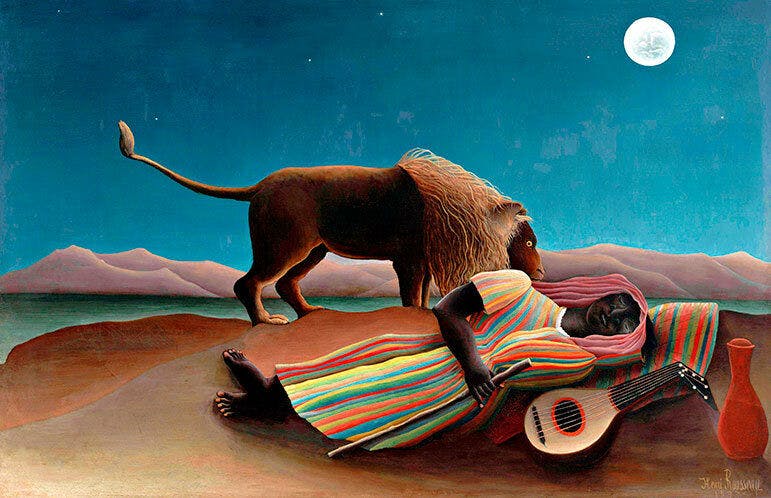

Subject matter

In general, the subjects most typical of the artist have the most value. Is the artist known for a certain style? Great! But for the most part, anything he or she paints outside that style won’t fetch as much.

How pleasing a painting is also matters. While difficult, unpleasant subjects are often important, a pleasant subject is more valuable because it is more sellable to a wider audience. Just like happy pictures on Instagram get more likes than “sad” ones (ugh), paintings that depict ugly subjects unfortunately don’t tend to do as well.

Cultural significance

Cultural themes ebb and flow like the tides. What was once considered out of favor could easily be significant tomorrow. The pendulum swings back and forth, and disproportionate gains can be made from timing a theme’s upward swing correctly.

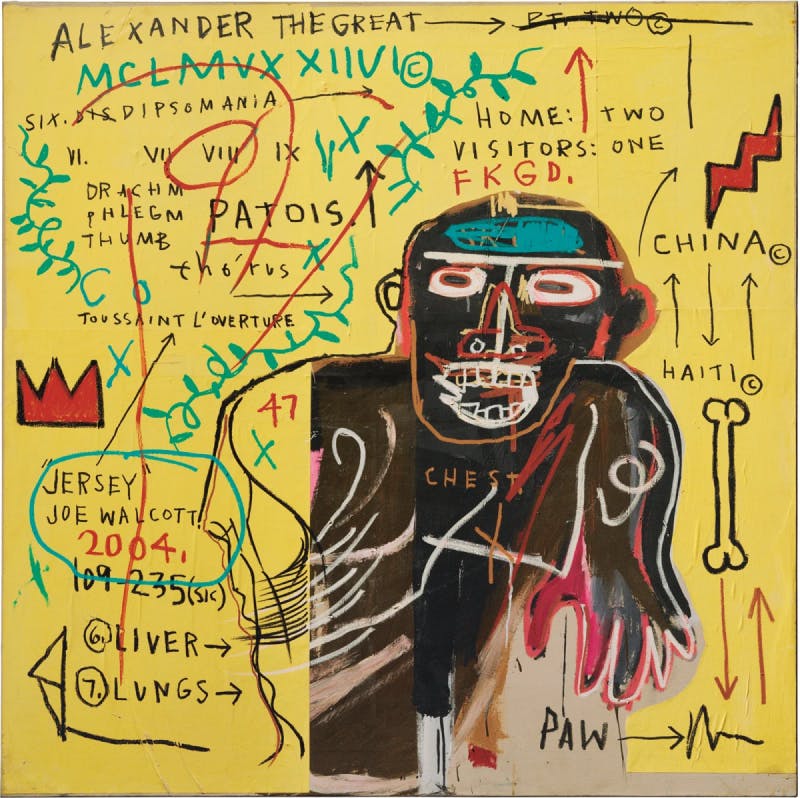

Take Jean-Michel Basquiat, for example. A true revolutionary, Basquiat painted wild, emotional, eccentric paintings with themes of social & racial justice throughout the 1970s and 80s. Ever since the Black Lives Matter movement has gained steam nationally and turned into a global movement, Basquiat paintings have been in extremely high demand.

It feels incredibly awkward to view such important moments in history through an investing lens, but at a minimum it helps one understand the significance of these cultural movements even better.

Size

Just like in real life (ahem) size does matter. But not necessarily in the way you think! While bigger is generally better, paintings that are too big to hang anywhere are considered less desirable than other large paintings.

Condition

Condition is also very important in the value of an artwork. Unlike with say, sports cards, there is no single, globally recognized grading system for artwork.

Ideally, a painting on canvas should be on the original canvas and not one that has been relined. Relining is when the back of an old painting is removed, and then carefully “cemented” with fresh linen. Canvases are often relined if they are torn, or about to tear.

People want perfection. Paintings with damage will be less valuable than those without. Yet, paradoxically, any restoration or retouching diminishes the value.

Scarcity

This is a no-brainer. Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (???? one of my favorites) is the only painting like it in existence. It was never reproduced, and nothing exactly like it will ever exist again. There is a near-zero likelihood it will ever live anywhere outside a museum.

However, Auguste Rodin, the French sculptor of the famous The Thinker, didn’t just chisel once. Instead, he hired a team to create 22 replica casts, which were sold to museums and private collections, making him a very rich man.

Provenance

This is the “fluffiest” indicator of value, but it matters tremendously.

If a work of art has been in an important collection or exhibition, there is a premium added to the value. Often a very big one. Great works of art “should”, theoretically, have a history of ownership and record of inclusion in collections and exhibitions.

We see this dynamic play out everywhere. Power begets power. Money begets money. The guy who went to Yale and did nothing for 4 years, but in the eyes of the labor market, he still went to Yale. The Kardashians are “famous for being famous,” but they’re still famous. VCs pile into a hot startup, leading to a sky-high valuation. But because of the massive influx of capital, the company eventually grows into its valuation. It’s as powerful a rule as any other.

A painting may be worth $20m if it came from an anonymous collection, but if David Geffen once owned it, congratulations; it’s now worth $30m.

Interestingly, since art dealers have privileged access to auction houses and private exhibitions, savvy dealers can actually influence the value of an artist’s work by employing “provenance arbitrage” techniques.

Fractional artwork investing today

As with so many other alternative asset classes, the combination of technology and loosened regulation has opened up a world of new opportunity.

Being an artwork collector no longer requires a million-dollar buy-in. The brilliance of today’s art market is that an incredible array of works are now being fractionalized, and available to the public at more modest price points.

While you can’t hang these paintings in your homes, fractionalization allows novice collectors to try the waters before taking a major financial plunge

Masterworks

Masterworks is the most well-known platform for buying fractional shares of contemporary artwork.

With over $160m in funding, Masterworks is clearly leading the way in the fractionalized artwork space. They buy each painting outright, and allow anyone to invest in fine art, including non-accredited investors.

One thing Masterworks does incredibly well is track & share data. Their extensive price database holds decades’ worth of art sales history, and is now available to the public.

But despite what Michael stated on our recent podcast, they aren’t the only ones doing this. There is at least one other company that should be on your radar.

Artemundi

Founded back in 1989 as a fine art marketplace, Artemundi is now a blockchain-based trading platform for institutional and private investors. Collectors and art enthusiasts may buy and sell fractionalized ownership of blue-chip artwork, by buying Art Security Tokens (ASTs).

Artemundi has partnered with Switzerland-based Sygnum Bank, which facilitates access to digital marketplaces for tokenized artworks and lowers the entry barriers to the art market under Swiss banking regulations.

In addition to tokens, Artemundi also runs a few different fine art funds. The Artemundi Global Fund ran from 2010 – 2015, and put up some impressive numbers:

- $211m in artwork assets under management

- Net return (5 years): 85.36%

- Average net annual return: 17.07% per year

Conclusion

Ever since humans first created artwork, we’ve had art collectors. Collecting fine art is almost as timeless as artwork itself.

With the exception of 2020, auction houses have consistently reported YoY growth and new sales records, as new and seasoned collectors alike pour money into new acquisitions.

For some people, owning art is not only a way to show they have money, but it’s also a way to make it. Art is viewed as a financial product in many circles — another fun investment to capitalize upon. And this is being made easier with companies like Masterworks. Not only do people have increased access to the art itself, but they can also invest in more manageable amounts.

This trend will change the landscape of art investment dramatically. I think it could lead to increased commoditization of art, but it will also create positive growth in the number of people who feel they can get involved — people who may love art but have traditionally been priced out of investing in it.

But while the technology and regulations surrounding art investing have changed the game, the fundamental reasons for collecting haven’t. Beyond simply appreciating art for art’s sake, people collect artwork to signal status, culture, and taste.

And that’s a good thing. Artwork is meant to be displayed, meant to be discussed, meant to be shown off to others.

Art can certainly appreciate. But more importantly, we can appreciate the artists who work tirelessly to create timeless beauty from scratch.

One year ago…

On August 15th, 2020, we published our 4th issue on The Economics of ADUs.

Between rental income and increased property values from expanded square footage, I continue to believe “granny flats” present one of the most compelling opportunities in real estate — especially if you build in the ADU sweet spot.

I’ve been keeping my ears tuned for chatter on new ADU funds and other creative investing opportunities.