Consistency and cash flow

Last December, we took our first look inside the world of buying & selling music royalties. Since then, we’ve had a lot of requests from the community to go deeper on this topic — and for good reason. The rise of streaming and third-party apps has forever changed the music landscape, and great change often brings great opportunity.

But it’s not just the way that music is bought which has changed. The way music is sold and valued is changing as well.

Today, we’re doing another issue on music rights. This is one of the most exciting and underrated alternative asset classes out there. We’re starting to learn a lot more about it. And the more we learn, the more we like.

Let’s explore 👇

Table of Contents

Record labels are the original music rights investors

To be clear, ownership of music rights is nothing new. It has been a sought-after income stream going back decades. This is why record labels exist in the first place.

Record labels are the original music rights investors. They act like investment banks, but instead of giving money to the artist directly, they do nearly all of the heavy lifting.

Record labels pay for:

- Recording

- Production & studio time

- Artwork

- Distribution

- Promotion

- Music videos

- Radio appearances & airtime

- TV appearances

In a nutshell, labels pay for nearly everything except touring. Similar to Y Combinator and other startup accelerators, they provide value, and lots of it. Getting signed to a label is like plugging into pipeline. It kickstarts careers and solidifies the path forward.

In return, labels typically get 80% of album revenue, with 20% going back to the artist. Remember that, just like with startups, not all artists succeed. (In fact, most don’t.) So while a record label may not need to hit home runs to the degree that VCs do, you better believe they need to recoup their costs. The 80% take rate may seem high, but it’s what makes the endeavor worth it for them.

But times have changed. There are new ways for artists, record labels, and outside investors to make money from music. And as we’ll get into shortly, despite the negative press around streaming, the prospect of owning music rights has never been more intriguing.

Before investing though, you first need to understand exactly how people make money from music rights. This asset class is a bit more complex than others.

So let’s start by breaking down the different types of music licenses.

Types of music licenses

Music royalties are divided into six categories, each of which delivers different levels of royalties to the artists/rights holders.

Mechanical license

The most relevant (and generally lucrative) licenses are mechanical licenses. These encompass any form of compositional reproduction, whether it be from the sale of physical music (CDs, vinyl records, etc), or digital (purchased from iTunes, streamed through Spotify).

Mechanical licenses are the most broad-ranging rights available to musicians. Artist can even receive royalties from cover songs (although a portion of the cover’s royalties must be paid to the original composer). Critically, when artists make a deal with a record label, they typically sign away a portion of their mechanical royalties, but not their license. That is to say, they usually still own the rights to their own music.

But this is not always the case, and many artists have been screwed over by highly unfavorable deals. For example, Frank Ocean actually had to purchase back his recording rights from Channel Orange to get out of his contract.

Sync license

A synchronization license entitles rights holders to royalties made from pairing their song with another form of media. This usually takes the shape of a TV show, movie or ad.

Music is the glue that holds movies together. Think about the ending of The Graduate without Simon and Garfunkel’s wistful ‘The Sound of Silence’, Drive minus the pulsating synth-wave ‘Nightcall’, or Goodfellas without ‘Layla.’ None of it could’ve happened without sync licensing.

Performance license

A performance license allows musicians to claim royalties whenever their art is publicly played or performed. It is the most common license negotiated.

Basically, whenever your song is played out loud, be it by a cover band at a concert in Tennessee, or over the speakers at Office Max, technically speaking you’re owed royalties. Now, clearly lots of musicians don’t get anywhere near what they are owed. Can you really expect an independent bakery to be sued for playing a Taylor Swift song? C’mon.

But this is why it is vital for rights holders to team up with a Performing Rights Organization (PRO). These companies are charged with collecting revenue they are owed on their behalf. Artists will never get every penny they deserve, but you’d better believe Neil Diamond gets a cut each time ‘Sweet Caroline’ is blasted at Fenway Park (even though the audience does half the singing).

The most well-known PROs include BMI, ASCAP, and ApRo. We’ll touch on these in a future issue.

Master license

A master license entitles you to the actual raw sound waves involved in a song. If you need a master license, you also need a mechanical or sync license.

Master licenses are used in film & TV, as well as samples and mashups (although when using a sample, you typically cannot alter it in any way). By law, master rights holders maintain total control of the works. As an artist, owning your masters means everything. Sometimes, masters are sold or handed over to family in estate sales.

Scooter Braun, the music mogul who purchased Taylor Swift’s first six albums, purchased her masters then flipped them to Shamrock Capital in 2 years. Swift has been loudly critical of the deal, calling Braun a bully, and claiming she was never given an opportunity to buy the rights herself first.

Print rights license

The print rights license, which is often overlooked, refers to the notation and physical sheet music. Whenever this is reproduced, digitally or otherwise, the creators are meant to receive a royalty.

Theatrical license

As the name suggests, theatrical licenses are a niche form of music rights, often used in productions where a unique rendition of a song will be played.

So that’s a look at the types of licenses.

The next thing to understand is types of sales.

Types of sales

When thinking about music rights ownership, another thing to consider is the type of sale. Which rights you can purchase will typically depend on the entity or exchange you’re purchasing from. This could be an online rights broker (such as RoyaltyExchange) a publisher, record label, or even the artist themselves (this is where the best deals are found).

There are a few different forms of rights ownership: lifetime rights, fixed return rights, and fractional rights.

Lifetime music rights

Lifetime rights are exactly what they sound like — once you own them, you are entitled to royalties from whichever license purchased for the duration of the ownership (usually until you die or resell the rights.)

Fixed return music royalties

Investors can also purchase fixed return royalties. While this is typically cheaper than buying lifetime royalties, it is often less lucrative. Fixed return royalties operate similarly to a bond, except instead of ending after a fixed period, the rights ownership expires once a pre-defined royalty quota is hit.

For example, Royalty Exchange recently offered an auction for the fixed return rights to ‘Afro Soca Music’ by Timaya. Investors could bid on the opportunity to buy the Fixed Return of $73,333. This means that the investor would hold the rights until royalty payments totaled at least $73,333. How long this may take is variable. Depending on the music’s success, it could be as short as a year, or up to a decade or more.

This particular asset sold for $61,500, implying the investor will receive a monthly royalty distribution, up to a total profit of ~$11,833, when payments hit the $73,333 mark.

Timing is everything here, and investors are betting & hoping this will be shorter rather than longer. If it takes 1 year, that’s a 19% return. Great! But if it takes 5 years, that’s a far less impressive 3.8% annualized return.

Fractional music rights

Finally, another investment opportunity is via fractional licensing ownership. Just like with other fractional investments, fractional licensing gives investors the potential to diversify their portfolio without having to divulge a hefty lump sum that’s required for popular catalogs.

Investors may split their ownership with other investors, or the artist/label, who may require some retained equity. The new marketplace Vezt allows artists to put up their music for ISO’s (Initial Song Offerings), where investors can purchase a fractional stake in a song in exchange for a portion of royalties.

Streaming royalties

There can be no discussion of music rights without an understanding of streaming royalties.

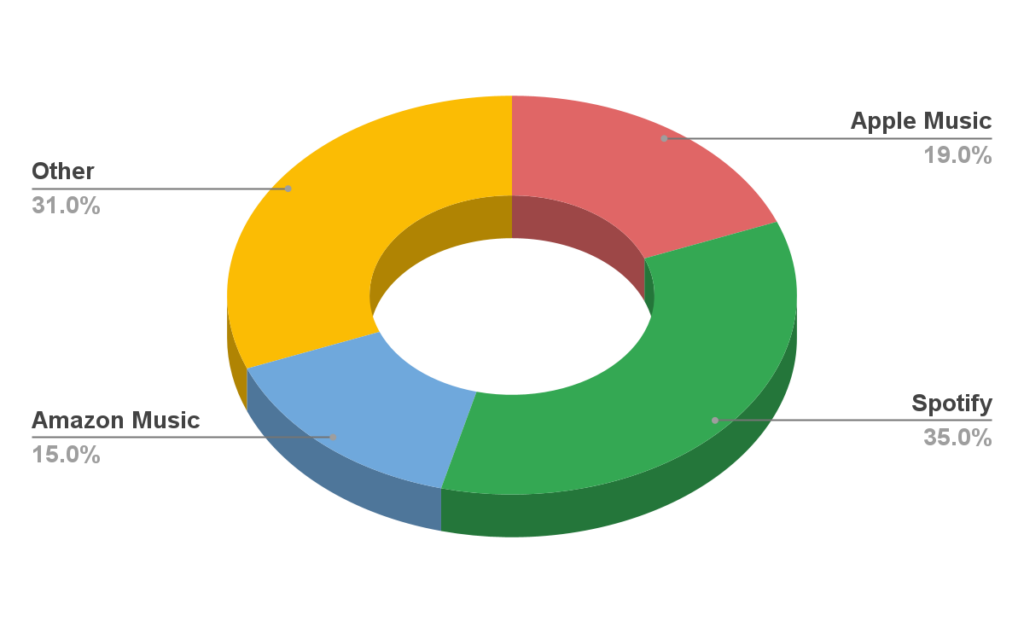

As we know, the vast majority of music today is consumed via streaming services such as Spotify & Apple Music, and less popular platforms like Google Play, Bandcamp, etc.

How much do artists earn from streaming?

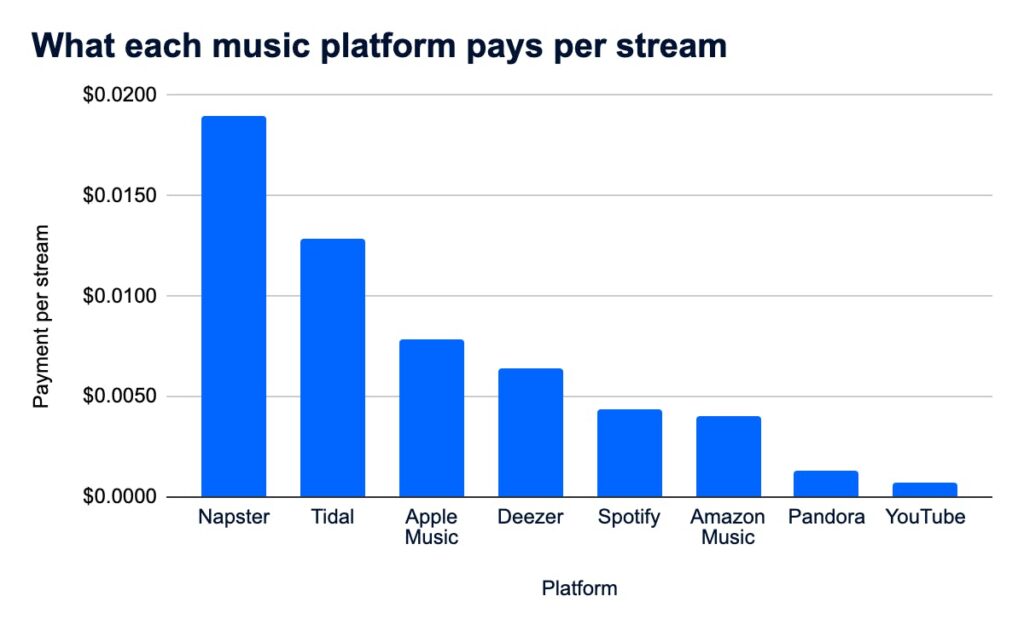

Music streaming services aren’t created equal. There is no fixed rule for how much each platform pays out per stream. There are lots of factors affecting how much money each stream spits back to the artist.

These include:

- Royalty rate. This is negotiated between the platform and label. Artist has almost no say in this.

- Free vs paid license. You wouldn’t think it would matter, but if a stream came from a paid user vs a free user, Spotify pays the artist more

- Location, pricing, and currency. What country the listener is streaming from. Songs on iTunes were far more expensive in Australia. Presumably the artists got paid more as well.

Now, the conventional wisdom around streaming is that it pays very little. And this is technically true. Artists typically earn less than half a cent per stream. In order to earn the median US wage from Spotify royalties ($78k/year), an artist would need over 1.4 million streams per month. That’s getting into “big artist” territory, no doubt about it.

I’ve put together a chart comparing roughly much each platform pays artists per stream.

But this is where it gets interesting. Over the past few years, music catalog valuations are up, even though COVID-19 has ravaged the live performance industry,

So this begs the question: If most artists make their money from live shows, how is this possible?

The reason for this is simple: Streaming revenues are remarkably consistent.

The consistency of music streaming

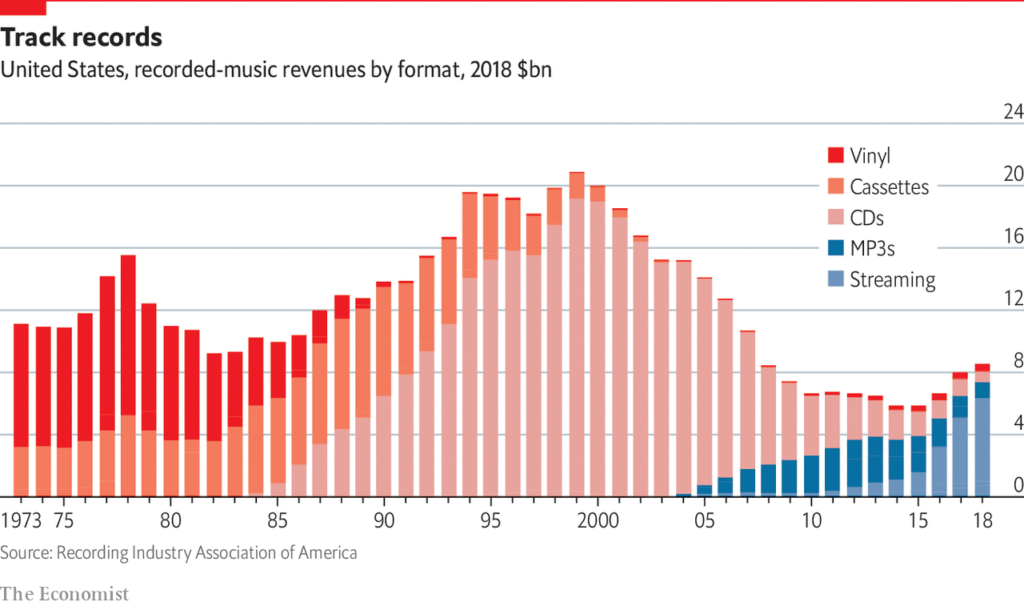

It turns out that the public perception of streaming royalties has been unfairly demonized. Yes, the per-stream rate is certainly low — especially compared to the per-album sales artists enjoyed back in the “glory days.”

But streaming is actually the major reason savvy investors are beginning to have confidence in discography valuations. They expect the value of music catalogs to continue rising for two reasons:

- Global streaming growth. In 2019, global music streaming revenue as a whole increased by 19.9%. It’s a good space to be in for that alone.

- Streaming provides a consistent revenue stream (sorry for the pun). It doesn’t have the same types of ups & downs records & CDs once had.

Since streaming is so frictionless, purchases don’t spike & fall the same way they used to. And this phenomenon plays out with both large and small artists. Self-published artists may never make huge money off royalties, but they make consistent money. That’s critical.

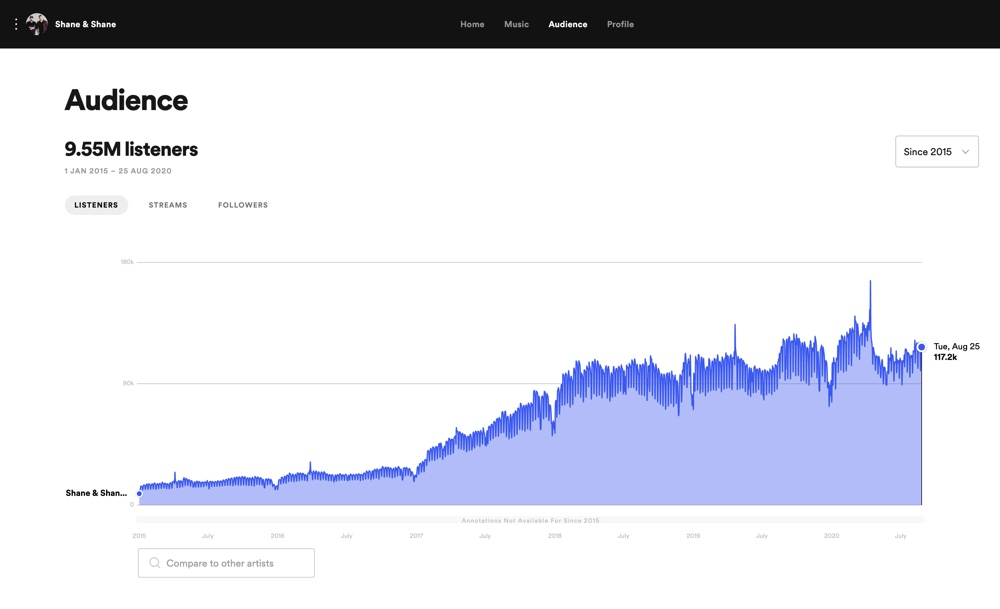

We can see this in the data. Spotify For Artists provides access to mountains of streaming data for every single artist on the Spotify platform. It gives you insights into an artist’s audience, location, and most importantly, the number of streams over time.

Looking through the data, what you quickly see is that, on the whole, artists’ streams tend to bounce along with the general rate of streaming growth.

Sure, some artists have an easier time of it than others. There are all sorts of expected variations along the distribution. But you tend to see stable lines, subtle upward and downward slopes, and the occasional big spike that tapers off at a “new normal.”

Unfortunately, not just anyone can get access to this data. You need to be an artist manager or record label to access Spotify’s “God mode.” But the data is clear: streaming produces consistent revenue. You see this trend over and over.

And anytime you have an asset with consistent revenues, you have opportunities for buyouts and fractionalization.

Streaming is changing the nature of songs

When you’re a huge artist with a loyal, long-time fanbase, you can sort of do whatever you want and still make money. However, newcomers have quickly learned to adjust their methods to maximize potential earnings.

Spotify pays by the song, but the listening duration can influence the amount paid per listen. A musician will usually earn more from getting 1,000 listens on a 3-minute song, than 500 listens on a 6-minute song. Musicians, A+R companies and record labels have all recognized this.

The result? Songs are getting shorter, and the number of albums released each year is falling. It’s much more efficient for independent artists to release short singles — especially those who don’t often play live. Albums can take years to complete, are expensive to produce, and usually have one or two good songs anyway. Streaming is agnostic to all that.

Given all of the focus on music streaming revenue, you’d be excused for thinking that physical sales (particularly CDs) are dying. And for the most part, they are all but dead — a mere 12% of what they were just a decade ago.

However, the rapid decline of CD sales hasn’t signaled the end of physical music sales. In fact, vinyl is making quite a serious comeback. Perhaps it’s nostalgia, perhaps it’s due to hipster culture, or maybe to the fact that vinyl has more warmth, richness, and depth than digital music.

Whatever the reason, vinyl records have come roaring back into fashion. In Australia, CD sales and vinyl sales are now aligned for the first time since the 90s. Prominent industry analysts believe that 2021 will be the year that Vinyl sales actually eclipse CD sales.

Other nations have attempted to prop up the CD industry. In Japan, CD sales still account for a massive 78% of music revenue, through incentives, prizes, and competitions, where winnings fans can spend a night with their favorite pop star.

How do you value a music catalog?

So, how do you analyze the potential future value of songs?

According to data from Shot Tower Capital, music catalog valuations have doubled over the past decade.

Global music industry revenue declined 19% during the ‘MP3 Era’ (2006 – 2015). However, this has reversed dramatically in the past five years, climbing 38% since 2015. Heck, the indie music market alone grew 27% between 2019 and 2020.

It’s gotten to the point where the question isn’t ‘Will the music industry grow?’, but instead, by how much? Different experts have different growth projections, with some more optimistic than others. Goldman Sachs has projected 100% revenue growth over the next decade.

This trend of revenue growth in the music publishing industry appears set to continue its upward trajectory. But while this data gives us insight as to industry trends, it doesn’t exactly tell us how to value specific catalogs.

Here are the biggest factors influencing music’s value.

Artist popularity

The prime determining factors of valuation are how popular an artist is, and the weight of their catalog (how many songs are being purchased each year.)

Genre

In terms of market share, we know that indie music is on the rise, whereas Latin music is stagnating. So all else being equal, an indie artist’s catalog would likely be worth more than a Latin music artist.

Revenue diversity

Investors must consider the proportion of income that comes from streaming.

For example, a musician who earns 97% of their revenue from streaming platforms would be more appealing than a musician who split it 60/40 with merch sales (unless you are buying the exclusive rights to their merch as well.)

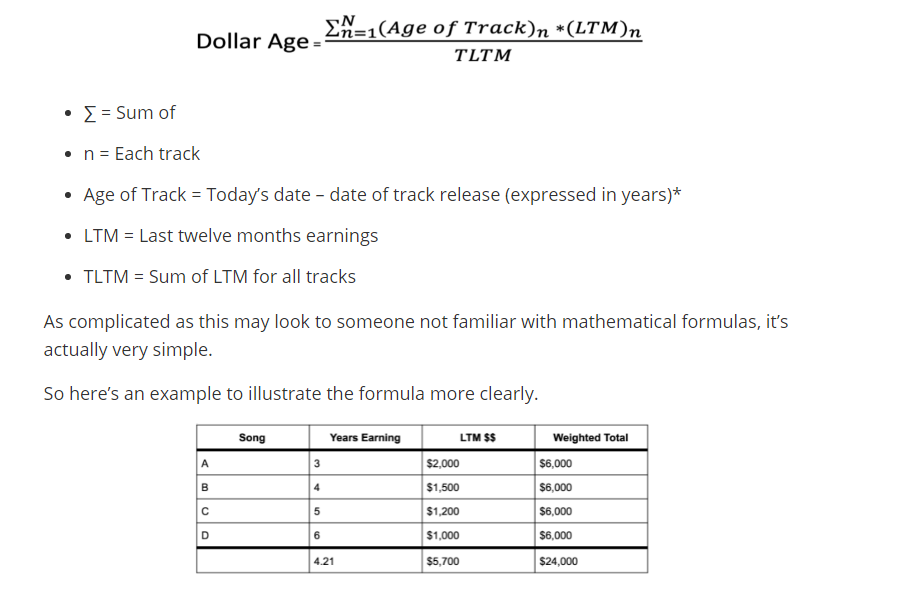

Dollar Age

The time value of money is especially important in this world of consistent streaming and fixed return rights. An important concept to know is called dollar age.

The dollar age attempts to quantify an answer to the question: “How long are these royalties likely to continue in the future?”

There’s a tendency for investors to focus on recent history — looking solely at 12-month past performances and short-term projections. While this accounts for current fame and chart positions, this isn’t necessarily the most unbiased, measured way to look at the potential earnings of a catalog investment.

For example, take One Direction’s “What Makes You Beautiful.” At the time of its release, it dominated the musical world, topping the charts in pretty much every English-speaking country. A decade later, the song is still wildly popular, but its presence on radio, streaming services and TV shows has diminished substantially.

Conversely, Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust” was never even intended to be a single. 40 years later, it remains Queen’s best-selling track and has double the monthly listeners of “What Makes You Beautiful.”

Queen is a bit of an extreme example given their immense fandom, but the lesson is the same — investors should be looking at the long-term performance (over 7 years) as a demonstration of sustainable earnings. Observing the trends of royalties over a multi-year span takes most of the noise & guesswork out of the equation.

Royalty Exchange has even come up with an equation for prospective investors to figure out the worth of a catalog using Dollar Age as the key metric.

Simply put, each new day someone listens to a song, the more likely it’s going to be listened to again the next day. Just like with startups, getting in early and buying a stake before it balloons in value is ideal. But it’s also easier said than done.

That’s what Dollar Age helps synthesize. It’s essentially a model that helps you understand a catalog’s future stability

As the investing adage goes, “past performance is no guarantee of future results.” But it certainly helps.

Conclusion

No matter how many people shout from the rooftops about the death of the music industry, all the data suggests the future is extremely bright.

The continuing and consistent growth of streaming, coupled with the development of new distribution and royalty services, has broken down the monopoly once held by the “evil” record labels, who are even seeking new & creative ways to get a piece of the pie themselves.

I think what I love most about music rights (specifically mechanical rights) is the fact that it yields immediate and consistent cash flow. In this age of speculative meme stonks and million-dollar NFT rocks, we often forget how important fixed income is to constructing a portfolio.

So much time & attention is paid to asset classes that rely on future appreciation. Sports cards, video games, and sneakers are great assets to own for other reasons. But they don’t spin-off any cash! With music royalties, you get the best of both worlds: An asset that delivers consistent revenue and is likely to appreciate over time.

Most importantly, you get to put your money into something you love and truly believe in. This is going to be a terrific future alternative asset class.

But don’t just take my word for it. Wyatt found this job posting indicating Rally is quietly getting into royalties. And Otis just added Music Rights to their Discord.

Oh, and just two days ago, electronic artist 3LAU announced the launch of Royal.io — a revolutionary new way to invest in artists through the blockchain, while also providing financing and liquidity for artists. Amazing!

This alone warrants a deeper dive in the future. But we’re out of space for this issue.